The homesteading era in the United States began in 1862, when Congress passed new provisions for the settlement of public land under the Homestead Act. Under the terms of this act, by paying modest fees (originally a $10 filing fee and a $4 application commission) US citizens (or those who were intending to become citizens) who were either a head of a family, or single and over twenty-one years old, could claim 160 acres of public land available for entry. If married, a couple could double the claim to 320 acres. Once a claim had been made to the local General Land Office, the entrant was required to live on the land for five years, and carry out certain "improvements." Improvement was usually judged by the evidence of residence, whether living quarters of a certain size had been built, and the cultivation of a percentage of the land for agricultural crops. A claimant had seven years to fulfill these terms if they didn't abandon the homestead. If after paying a $4 final proof fee the claimant had "proved up" in the judgment of the Land Office agents, a land patent or title to the land was granted. In the decades that followed Congress amended and expanded the scope of homesteading legislation with such supplemental laws as the Timber Culture Act, the Desert Lands Act, and the Expanded Homestead Act. Over the next hundred years some 2 million applicants tried their hand at homesteading. About forty percent proved up, and gained title to 273 million acres across thirty states. Technically, this was homesteading.

Many Americans took this principle into their own hands by occupying western lands beyond federal surveys and often beyond United States authority with the assumption that their legal right to the land would eventually follow. Although the government hoped to control land settlement with proper surveys and titles, in many cases, particularly in the northwest, the squatters' presumptions were validated. The Donation Land Law passed in 1850 granted every male citizen (or who had declared their intention to become a citizen) over the age of eighteen in the Oregon Territory who had cultivated land for the past four years a half-section, or 320 acres. In addition to conferring legal ownership to earlier squatters, the law encouraged settlement by granting 160 acres to those arriving in the territory between 1850 and 1853 (later extended to 1855). Married settlers could double their acreage by securing another claim in their wives' name. An amended form of the Donation Land Law was eventually extended to the Washington Territory after it split from Oregon in 1853. Although the Donation Land Law had a limited area and time period of application, it was an important test case and predecessor to the Homestead Act, and established a tradition of free land grants in the northwest.

From the early days of the republic federal land policy brought many of the hotly debated political issues of the day into the foreground, particularly the question of whether slavery should be extended into the territorial lands of the West. Plantation and conservative slave-holding interests viewed the settlement of the West by thousands of homesteaders establishing small farms as an anathema. Against such opposition, prominent spokesmen including George Henry Evans, Horace Greely, and Galusha A. Grow argued that the availability of free or cheap land under the right terms would relieve the eastern states of the burdens associated with a surplus landless population, encourage the settlement of public land and the growth of new States, generate federal income, spread the public lands among many rather than few hands, and provide opportunity for any citizen (sometimes qualified in racial terms) willing to take up farming. A number of homestead proposals were presented to congress between 1830 and 1860 but were defeated by slavery interests or presidential veto. Secession of the southern states in 1861 removed the main opposition, and a Republican congress easily passed the Homestead Act in 1862.

Homestead law forged a compact between people and the land. Its terms revealed many characteristics of its authors; their politics, their economic theories, and their cultural attitudes toward settlement. As one historian of public land law put it, "the Homestead Act breathed the spirit of the West, with its optimism, its courage, its generosity and its willingness to do hard work." Yet if the act was proof of a commitment to improving the prospects of its citizen farmers, it was also proof that the land itself and its former occupants figured less significantly in the bargain. The law attempted to apply one format for farming in a vast territory of different soil conditions, climate, and topography. What may have seemed adequate acreage in Ohio or Georgia to support a farm proved untenable in many areas where the act applied, such as the eastern counties of Nebraska where rain fell in short supply. Because few states possessed a greater variety of landscapes and climate than did Washington, the state showed in a microcosm many of the problematic aspects of applying the Homestead Act to an uncooperative land. The diversity of environment was in turn a distinctive characteristic of homesteading in Washington, particularly in the Olympic Peninsula. Here on the far western edge of Washington was a landscape varied by massive old-growth forests, mountains, rain forests, river valleys, and rocky coastlines. Those coming from east of the Rocky Mountains to seek claims among the tall cedars, firs, and spruce faced the daunting task of clearing enough land to fulfill the terms of homestead law. In this context, agricultural clearings were more than spaces in the woods. Farmlands hewed from the timbered claims in the Olympic Peninsula stood as tangible markers of the complicated and multifaceted legacy of homesteading in the United States. As a crucial requirement of "proving up," clearings reflected a federal policy that mixed several competing elements, including an enduring faith in supporting the small independent farmer and a bureaucratic framework and approach to land management. As evidence of the effort put forth to farm on difficult lands, clearings showed the lure of the homesteading in America. That hopeful settlers tried to make a space and life for themselves among the forest giants of the mountainous Olympic Peninsula testifies to the strength of this ideal.

The Homesteading Era Begins

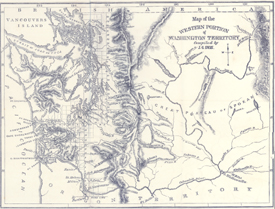

When the Homestead Act became law in 1862, the area that later comprised Washington state had territorial status. Formed in 1853, Washington Territory encompassed an expansive area soon cut back by the establishment of the Idaho and Montana territories in 1863 and 1864. One of the first to file for a homestead claim in Washington Territory was Irish-born James Langon. When Langon arrived in Clark County in the mid 1860s, the territory was mostly populated by a diverse number of Native American tribes and a few thousand Euro-Americans. Native tribes occupied lands that spanned the territory, a mosaic of linguistic and cultural groups that stretched from the Olympic Peninsula to the Palouse. Although tribes had varying degrees of itinerancy, many resided near watersheds or coastal areas. Euro-Americans were grouped primarily in small mill towns near the Puget Sound and scattered settlements along the Columbia River. Earlier Euro-American settlers had gained title to lands through a various means, whether under pre-emption laws, cash sales, war service scrip or the provisions of the Donation Land Law.

Prospective homesteaders that followed in Langon's footsteps to Washington Territory over the next two decades would find settlement in a state of flux. Homestead entries were supposedly limited to certain government surveyed lands. Major government surveys of the West were just beginning in the late 1860s. Military and railroad surveys were underway, but mapping the Washington territory was still far from complete by the time statehood was achieved in 1889. Other groups with designs on the land, missionaries, the military, squatters, prospectors, miners, timber interests, stockmen and railroad companies vied for and secured space in the territory. Many chose not to wait for surveyors and shrugged aside any native claims to the land, following a long pattern of westward encroachment.

Contact between native tribes and Europeans in the Pacific Northwest had a long history, but the arrival of Euro-Americans fundamentally changed the nature of rival claims to the area. Earlier the British presence in the Pacific Northwest had largely been mediated through the Hudson's Bay Company, which had developed relationships with the region's native population based on trade and the procurement of furs, but Americans, or "Bostons" as they were sometimes known, began to come to the Pacific Northwest as intent on settlement as they were on resource extraction. After displacing Britain in the lands south of the 49th parallel, the United States entreated with native tribes to gain possession of the land, a process that was complicated by different conceptions of entitlement and ownership. Native frustration with the treaty experience was only exacerbated by U.S. land policy, which rewarded squatters and encouraged immigration to the Northwest. Resentment periodically flared into war between 1855 and 1879, making homesteading in the territory during this period a potentially dangerous undertaking. Relentless military campaigns ended the era of violent resistance, and native tribes were left only with lands demarcated by the reservation system. Even these last enclaves were not sacrosanct. Periodically the reservations were reduced in size or otherwise made available through legislation such as the General Allocation or Dawes Act (1887). The Colville Reservation, for example, lost the northern half of its area when its member tribes voted to cede the land for $1.5 million in 1891 (payment for which was finally authorized by Congress in 1905). Other Colville lands became available for homesteaders in 1916 under the provisions of the Dawes Act.

As native tribes saw access to their traditional lands increasingly diminished, the number of Washington homesteaders grew. Several developments in the 1880s contributed to a settlement boom in the last two decades of the century. The first transcontinental trains reached Portland in 1883, and soon railroads extended into Washington as well. By the turn of the century steamships were operating on the Columbia River and the Puget Sound, and the Great Northern Railway offered service to the Midwest from Seattle through Spokane. While transportation networks were in the course of development, Washington achieved statehood in 1889. With better political representation and the benefits of statehood, the prospect of settlement in the relatively unpopulated northwest corner of the country became brighter. At the same time, the emergence of "dry farming" methods provided an approach better suited to the semi-arid regions of Washington's central and eastern counties. In contrast to older states, the newer areas of the West like Washington had a higher percentage of farms started by homesteaders. The Tenth Census of the United States of 1880 recorded 6,529 farms in the Washington Territory. Five years later, the Government Land Office put the number of homestead final entries in the territory at 5499, indicating a high presence of homesteaders among Washington farmers. Prospective homesteaders, and many others, continued to flood into the state through the turn of the century. Between 1900 and 1910, the population of Washington increased over 120%, the highest growth of any state in the Union over this decade.

The Homestead Era Amended

When James Langon filed for his Clark County homestead in 1866, he was part of a relatively small group of Washington Territory homesteaders taking advantage of the Homestead Act in its early years. As reports of abuses, deficiencies and conflict accumulated, a series of additional legislation was passed to improve homesteading in difficult parts of the West. The Timber Culture Act (1873) granted homesteaders and other entrants an additional 160 acres of land if they planted and cultivated at least 40 acres of trees within 10 years. The purpose of this act according to historian Paul Gates was threefold: "to get groves of trees growing in the hope that they would affect the weather and bring more rainfall, to provide a source of fencing, fuel wood, and building materials in the future, and to provide another method by which land could be acquired in areas where larger units than the usual 160 acres seemed necessary." Although many parts of Washington clearly had little need for planting additional trees, some counties east of the Cascades mountain range where trees were far less common were opened to Timber Culture claims. Many who obtained land under this act later sold the claim as a relinquishment. Selling a relinquishment may have been contrary to the law, but it was a common practice that earned early comers the funds to make a better start on other claims. Critics pointed to the ease with which speculators used the Timber Culture Act to acquire land as a major deficiency, and the act was later repealed in 1891. Another complement to homesteading laws that applied to the semi-arid central and eastern parts of Washington was the Desert Land Act, passed in 1877. This act intended to promote agriculture in drier regions by offering cheap land for those able to irrigate and cultivate a portion of the claim. Eligible claimants could pay $0.25 an acre for up to 640 acres of non-timbered, non-mineral land not producing grass provided they could prove within three years that at least one-eighth of the acreage had been reclaimed. After fulfilling these terms, the claimant paid $1.00 more per acre and the title was theirs. Of the many thousand who filed for claims under the Timber Culture and Desert Land Acts, far fewer gained patents - that is, the land was often more valuable for sale as a relinquishment, too difficult to prove up, or acquired by fraudulent methods.

Despite these various attempts to increase the number of acres available for homesteaders in places where farming was more difficult, the standard claim under the law was still 160 acres in most cases. The Enlarged Homestead Act (1909) addressed the size problem by allowing entries of up to 320 acres, which sparked a dramatic rise in the number of entries. Passage of the act represented a victory for the homesteading forces against the stockmen, who were pushing for larger 640 acre allotments more amenable for grazing. The political battle over the Enlarged Homestead Act illustrated some of the challenges that homestead policy had faced since the mid nineteenth century. With the vast resources of the public domain at stake, homesteading was but one concept of land use situated within a number of competing ideas.

Even with the prospects of farming improved by larger allotments, by 1909 much of the better agricultural lands had been taken. Potential homesteaders in Washington were forced to more marginal areas such as the Olympic Peninsula or took advantage of the opening of reservations for claims. One of the last pieces of legislation intended to facilitate homesteading was prompted by fears that better land was available in Canada on easier terms. In 1912 changes to the homestead law enabled a claimant to gain title in 3 years instead of 5, and permitted a 5 month residence exemption as many homesteaders sought employment elsewhere to supplement their farming efforts.

While homestead and farming interests had long enjoyed support from powerful political advocates, a growing concern for the conservation and preservation of the public domain in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century posed a potential threat to future homesteading. In 1897 President Grover Cleveland established the Washington Forest Reserve, which set aside some 3 million acres of forest lands for federal management. Soon other parts of Washington were withdrawn from public entry by the establishment of national monuments and parks, such as Mount Rainier, designated the nation's fifth national park in 1899, and Olympic National Park, first protected as a National Monument in 1909 and later granted National Park status by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1938. The shift in federal land policy generated some backlashes. As a result, some areas were reopened for homesteading and other development, either within federal lands as provided by the 1906 Forest Homestead Act, or through reductions in park size. The reserves and parks gave the federal government the opportunity to put the principles of the emerging conservation movement into practice, but little infrastructure development followed within their boundaries. To some, the isolation from markets and urban resources was a mortal blow to the prospects of a successful farm. In the Olympic peninsula more than half of the homesteads affected by the new reserve status sold their claims for whatever they could get or simply abandoned their rough wood cabins and hard-fought clearings. Those who chose not to leave faced an extended government campaign to add any private holdings within the national parks to the public domain, sometimes through the right of eminent domain. The extension of the Olympic National Park in 1953 to a portion of the western coast forced many homesteaders to give up their land. Nearly a century after passage of the Homestead Act, the removal of western Washington homesteaders testified to a new set of imperatives guiding federal land management.

Roughly a century after James Langon, in 1969 Marvin Grillo was granted the last title in Washington under the terms of the original Homestead Act to his claim in Okanogan County. Several years passed before the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 officially ended homesteading in the United States, with exception of a 10 year extension to claims filed in Alaska. The many flaws and abuses of the Homestead Act provided ample opportunity to debate its success, but its significance for Washington state is difficult to dispute. As a land policy, homesteading promulgated terms by which different peoples came into contact, generating a range of adversarial and cooperative relationships. The lure of homesteading attracted immigration, encouraged the growth of communities, and increased taxable property. Homesteaders contributed to the environmental changes that accompanied American methods of farming by accelerating the development of mono-crop agriculture, altering habitats, introducing new species, and reshaping landscapes. The chronology of homestead legislation documents the various attempts to adapt a standardized federal formula to the diverse lands of the West, but the lives of those that used the law to settle in Washington document a more personal history, one that provides the essential details of how federal policy was translated in a regional context.

Those contemplating a move to Washington had a variety of sources of information about the region at their disposal. During the territorial era, there was little shortage of optimistic descriptions penned by the many groups hoping to encourage emigration. In "A Circular Letter to Emigrants Desirous of Locating in Washington Territory," the territory's first governor Isaac Stevens hailed Washington's

vast natural resources, hoping to attract a sufficient number of settlers to put the territory on a path to eventual statehood. Others with a keen interest in marketing the territory included railroad companies, land speculators, and later, logging companies, each intent on selling their land

(logged-off lands, in the case of logging companies) to settlers. World's fairs also showcased the bountiful natural resources and agricultural potential of Washington, perhaps sparking for some

visitors a vision of a farmer's paradise.

While many saw opportunity in such laudatory accounts, there were other reminders that it might be the kind of opportunity born of a region considered undeveloped by most Americans. On a tour of the Puget Sound in 1883, reporter Helen Hunt Jackson found in the area "the wilderness is dominant still. Vast belts of forest and stretches of shore lie yet untracked, untrodden, as they were a century ago…" While Washington east of the Cascade Mountain range differed greatly from the Puget Sound, Hunt's description certainly rang true of the Olympic Peninsula. A booster from Clallam County tried to spin the area's lack of development as untapped potential and the heavily timbered, mountainous ranges as gorgeous scenery. However, he stopped short of falsely representing the country as a "farmer's paradise" as unscrupulous "real estate sharks" had done. Instead, he advised "all to come and see, without imagining that we live in a land free from forests and stumps; come and investigate our natural advantages and make all you can of them, and we assure you that you will make your home among us and be satisfied in such a favored land."

Although such accounts hinted at the obstacles that farmers might encounter in the northwest corner of the nation, other reports of fertile soils and temperate weather were motivation enough for some like the Boe family, who left their homestead in South Dakota, dried out by the hot summers and frozen by the cold winters, to find better climes farther west.

Whatever the reason, homesteading hopefuls came from a variety of states and countries. With only the intent of future citizenship as a requirement, European immigrants comprised a notable percentage of Olympic Peninsula homesteaders. The Lake Ozette area had concentrations of Swedes, and an area near the confluence of Thunder Creek and the East Dickey River became known as the "Polish Settlement." Austrians Anton and Jospha Kestner took up a claim in the Quinnault Valley, and German immigrants included Theodore Klahn, who came to Dickey River in 1892, and Beaver Prairie homesteader August Konopaski. Very few non-European immigrants, however, could be counted among the homesteaders. Virginia Ketting remembers a sprinkling of Chinese farmers in the Port Angeles area, but they did not own title to land. Instead local farmers worked out various tenant arrangements with the Chinese, such as exchanging the labor of clearing fields for two years worth of crops. Under the terms of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, Chinese were ineligible for citizenship and thus could not apply for homesteads.

Homesteaders may have been steered to the Olympic Peninsula by word of mouth or to join family members, others may have read US Department of Agriculture bulletins that advertised homesteading opportunities in various states. Prospective homesteaders could also look to several guidebooks to find practical information about exactly how to file a claim, the different options available for obtaining land, how to prepare for a successful homestead, and how to pursue legal action in the event of a conflict.

The Homestead Act was not the only legislation passed in 1862 that facilitated the settlement of the West. In that year Congress also approved the Railroad Act, which set in motion federal subsidization of the nation's first transcontinental railroad. Land grants, the cornerstone of western settlement strategy, were put to work for the railroads. Some seven years later in 1869 the first transcontinental line was completed, yet not until late in the nineteenth century did the rail networks spread into the Pacific Northwest past Portland, Oregon. Transportation to homestead claims in Washington Territory often involved arduous journeys, an ordeal that changed little during the peak years of the Homesteading Era. Overland travel relied on military roads, wagon trails or trailblazing. To reach his claim in Clark County, James Langon likely came by way of the Pacific Ocean and the Columbia River, landing at Fort Vancouver and proceeding north from there by horse or on foot. Obtaining goods, bringing crops to market, and access to schools and hospitals remained difficult for many settlers well into the twentieth century.

This was especially true of the Olympic Peninsula prior to the 1930s. Regional tribes such as the Makah, S'Klallam, Quileute, Hoh, and Quinnault had long traveled over well worn trails and by canoe. Euro-Americans adopted these methods, and coming in increasing numbers in the 1890s, began to develop different transportation networks as well. But even as ships and railroad service reached the outer fringes of the Olympic Peninsula, travel into the interior was left to horse, canoe, and foot. Although logging railroads began to snake inland into the dense forests, roads were largely limited to connections between coastal towns.

Despite the remote location and lack of developed roads, the automobile and truck took root in the Olympic Peninsula during the WWI years, when farming and logging enjoyed a relatively high period of prosperity. As elsewhere in the United States, Ford's Model-T was a common purchase. Affordable, tough, and easy to fix, the Model-T could travel on rough roads and even be put to work on the farm. The local automobiles of the West End were a frequent subject for Mora photographer Fannie Taylor, whose photos captured the growing popularity of the automobile in the early twentieth century. The increasing numbers of car owners provided a new impetus for roadbuilding, and the effects began to appear in the Olympic Peninsula in the 1920s and 1930s. Progress on road construction, however, was slow. For many years car owners negotiated single lane, unpaved roads or worse. In 1931a paved loop road around the perimeter of the peninsula finally provided an arterial link between the region's communities and western Washington, but by this date homesteading opportunities in the region had largely disappeared.

One of the first projects for any homesteader was the construction of a residence. The law stipulated that a domicile suitable for permanent residence of at least 10 by 12 feet with a minimum of one window must occupy the property. Most of these homes were built with either logs, sod or cut lumber, depending on what material might be easily at hand. Living quarters on Washington homesteads were almost exclusively built with wood. Log cabins required few tools and no nails, but needed a ready supply of logs and were better suited to smaller houses. Many homesteaders chose plank houses or shanties instead, for several reasons. Washington had a ready supply of trees and numerous mills, especially in the heavily forested areas near the Puget Sound and on the Olympic Peninsula. Homesteading in Washington began in earnest later than many other states, the bulk coming after railroads had connected Seattle and Spokane to the Midwest, which provided better access to construction materials and tools needed for cut lumber homes. Plank homes were easier to add on to, and more mobile. It was not unheard of for homesteaders to move their home to a new claim if abandoning an old one. Unfortunately for those living in areas with colder winters, the plank homes were harder to heat.

As the accompanying photographs suggest, homestead houses ranged in terms of size and sophistication, from Lars Ahlstrom's simple one room cabin to Marge and Charley Grader's multistory plank house. Construction rarely ended with a finished house. After fulfilling the basic residence requirement, homesteaders built barns, corrals, fenced gardens, smokehouses, crop storage facilities, and larger houses.

Converting a claim into farm was often one of the greatest challenges facing a homesteader, particularly for those taking forested claims in the Olympic Peninsula. The farmer's first task, clearing the land for planting, varied greatly depending on local geography and vegetation. The Olympic Peninsula homesteader often had to contend with massive cedar, spruce, and fir trees. In much of nineteenth-century America, clearing land of trees was largely accomplished by the long-standing method of "slashing and burning." This entailed felling trees with an axe, piling the debris and putting it to fire. Stumps were burned, left to rot, or pulled out with levers, mattocks, and peaveys, sometimes with the assistance of animal power. Some chose the slower method of "girdling" trees by removing a circumferential layer of bark and the outer sapwood layer of the tree through which the vital nutrients passed. This shallow cut killed the tree but left it standing until it succumbed to weather and decay. Some of these techniques had been used by Native American Indian tribes for centuries; others methods were brought by European immigrants. By 1900 other technologies including stump-pulling machines and explosives began to see wider use in the stump wars. For those who could afford to buy or rent them, steam donkey engines, and later tractors and bulldozers, were the most effective means of clearing land - but these resources were not typically part of homesteading or farming in general before the 1910s.

From the wheat fields of the Palouse to the apple orchards of Clallam County, Washington's agricultural economy was marked by diversity. Soil and climate were central considerations in deciding which crops to plant, however, the development of different agricultural practices during the Homestead Era broadened the range of possibilities for farmers. The adoption of dry-farming techniques in the 1870s and 1880s in parts of Washington Territory, for example, opened lands in eastern counties formerly thought unfit for farming to cultivation.

| 1890 | 1910 | 1930 | |

| Washington state | 231 | 208 | 191 |

| Clallum County | 194 | 103 | 79 |

| Jefferson County | 139 | 120 | 96 |

The increasing mechanization of farming during the Homestead Era, especially in the early decades of the twentieth century, also contributed to the expansion and productivity of agriculture in Washington. Technological innovation was first concentrated on the tasks of cultivation which brought improved plows, harrows, seed drills, reapers, mowers, binders, combines, threshers into wider use. Later in the nineteenth century, new methods of motive power were developed. Animal power, which had been a fixture on farms for millennia, was supplemented by steam and internal combustion engines. Mechanization increased the capital costs and production capabilities of farming - in some counties, such as Clallam and Jefferson counties listed below, these trends were accompanied by a decrease in the average size of farms and an increase in the size of the largest farms. Science, which had long been applied to American agriculture, took new institutional forms in the agricultural research stations and university agricultural science programs established in Washington after statehood was achieved.

In areas where agricultural productivity was sufficiently high, a 160 acre homestead might send a portion of the harvest to markets; elsewhere, much of the farm was dedicated to subsistence. In the Olympic Peninsula counties of Clallam and Jefferson, just feeding one's family and livestock might demand considerable effort. Not only was the average size of a farm consistently smaller than the state average, less than thirty percent of these farms were usually "improved" acres - the portion ready for cultivation.

The 1910 Census reported that farms in Washington typically had 54.4% improved land, whereas only about 27% and 21% of Clallam and Jefferson county farms, respectively, were improved. This meant that the average land ready for cultivation in these two counties was only about 25 acres. Although Jefferson County led the state in the production of potatoes in 1890, it is not difficult to understand why in terms of number of farms, improved acreage, and value of crops the Olympic Peninsula counties were typically below most of the other counties in the state.

If the average Olympic Peninsula farms was smallish and often had to contend with more rainfall than other parts of the state, what did homesteaders tend to plant? A survey of more than eighty claims within the boundaries of the Olympic National Forest made under the terms of the Forest Homestead Act of 1906 showed that in this area, homesteaders usually started a garden and planted some fruit trees for home use, then established crops that worked well on small plots often interspersed with stumps and trees such as hay, root crops (mostly potatoes), and clover. In the river valleys, prairies, and less forested areas of the peninsula - climate permitting - other crops including hops, apples, wheat, and strawberries were common.

The task of inspecting homesteads in the National Forests for evidence of having "proved up" was given to the USFS rangers. Armed with a notebook and occasionally a camera, rangers recorded the progress of homesteaders, and made recommendations on whether or not to grant titles to the claimants. One such report provides a rough sketch of the life of a typical Olympic homesteader, Theodore Beebe. Beebe staked a claim in the Big Creek drainage in the southwest corner of the Olympic National Forest in 1918. Some five years later when under the terms of the homestead law he was eligible to apply for a patent to the land, he had built a rough house on the site for his wife and four children, had partly cleared three acres for cultivation, and had slashed two additional acres. Beebe managed to bring between 0.5 to 1 acre of land into cultivation per year, planting oats, timothy, clover hay, potatoes, and garden truck. Stumps still remained on some of the cleared land. The ranger's report noted that "all clearing, cultivation, and slashing was done by the claimant." It is likely that claimants were quick to claim sole responsibility for performing such work, as it no doubt underscored their "good faith" effort to bring the land into cultivation - a key requirement of proving up. Beebe had one horse, and it is possible that he used the horse to pull stumps and plow. Homesteaders nearly always kept some number of cattle, horses, poultry, sheep, or swine when possible. The ranger estimated the average cost of clearing Beebe's land to run about $100 per acre, and when cleared, to be worth about $75 per acre.

The 1920 census showed that Olympic Peninsula farms were still growing the crops such as oats, wheat, hay, potatoes, strawberries, and apples that had characterized the region's agricultural production for several decades. By the 1930 census, the region's agricultural economy had moved toward dairy, poultry, and animal specialty. Clearing the land for the cultivation of crops was waning in the last years of homesteading on the peninsula.

Making a homestead into a cash earning enterprise was a difficult task. Money to support life on the homestead often came from other sources of employment, depending on what was available in the area. In forested regions, homesteaders took jobs as loggers, mill hands, and timber cruisers. Government provided other opportunities, such as mail carriers, surveyors, or United States Forest Rangers. Some worked as miners, commercial fishers, bounty hunters, packers, or on road construction crews. William Taylor supplemented the homestead he purchased with funds brought in from operating a general store; his wife Fanny was the local Post Office Mistress. Near his homestead claim, Robert Getty founded a town that within a few years boasted a hotel, warehouse, boat house, school, cemetery and US Post Office. Similarly, after receiving title to his homestead claim in 1895, Frank M. Ackerley divided his land and sold lots as the future townsite of Sappho. In areas more dominated by farms, homesteaders worked as hired hands.

Although the creators and supporters of homestead law conceived of homesteads as sufficient in themselves to support a farming family, finding extra work could determine their success or failure. Most of those who took homesteads in the Wildwoods area of Lewis County in the 1880s, wrote one local resident, abandoned them by 1900 because "there was no opportunity to earn money, necessary to supplement Nature's bounty." Whether farming for subsistence or the market, homesteaders needed funds for a variety of items, from sugar to agricultural implements. Because proving up required a certain percentage of residence on the land, homesteaders were theoretically limited to the hours they worked off the homestead, but insufficient residence requirements were notoriously difficult to prove.

Many tasks of daily life on the homestead changed little during the Homestead Era. Heating the home, preparing a meal, clothing the body, or schooling children followed well worn patterns. Families often lived in close quarters, with little space for privacy. Household technologies provided some measure of life on the homestead. In Washington, instead of fireplaces, most homes had stoves for cooking, warmth, and heating irons used to press clothes. Gathering wood for the stove was a daily chore. In certain locations, windmills and tanks might supply running water, but more commonly water had to be hauled from wells, creeks, and springs. Without refrigeration or easy access to ice, perishable goods had a short life. Yet the homestead was not out of reach of contemporary technological developments, even if they arrived more slowly. As washing machines became widely available in the early years of the twentieth century, homesteaders purchased models that were suited to remote locations. Dorothy Kenney's house had a gasoline-powered washing machine, with a choke, a muffler, and exhaust pipe that was placed out the window. In 1908, the Peninsula Telephone Company began to string wires from Fork's Prairie to Mora and La Push, bringing somewhat sporadic telephone service to the west end of the peninsula until 1921, when hurricane-force winds destroyed the system. Electricity became available in Forks in the 1920s, but other rural locations in the peninsula and greater Washington were still without connections to larger grid networks into the 1940s.

A central feature of children's daily life on the Peninsula, like elsewhere in the United States, was the schoolhouse. Throughout the territorial years and the initial years of statehood, the development of the educational system in Washington was rather uneven. Land grants provided an initial means of support, but it was left to local property taxes and other sources of funding to provide the balance. Some equalization between the various counties was gained through passage of the Barefoot Schoolboy Law in 1895. Sponsored by populist John Rogers, the law provided for state funds for education to counteract educational imbalances between rich and poor counties. Despite sparse settlement in many areas, West Enders managed to establish several local primary and secondary schools.

Underlying the day to day routines was a sense of community, defined in part by relationships. Homesteaders often relied on their neighbors for work, food and social interaction. Depending on where one lived and where one had come from, factors such as ethnicity, gender, race and class played different roles in shaping relationships within a community. Some homesteaders had to adapt an immigrant's sensibilities to an American context, others encountered peoples of different ethnicities and race for the first time. The West End of the Olympic Peninsula, populated with citizens from various states, European immigrants and several native tribes, was a region of some diversity; consequently incidents of conflict, cooperation and mere tolerance were evident as the region's inhabitants learned to live with each other. Not surprisingly, rights to land could be at the center of antagonisms. West End settler Daniel Pullen was suspected to have burned the Quileute village near La Push in 1889 after they succeeded in their efforts to establish a reservation on his claim. On a day to day level, cooperation rather than conflict was the norm, as native tribes provided transportation, shelter, food, and labor. The important role of native tribes in facilitating homesteading in the Peninsula was captured by photographers such as Edmond Meany, Bert Kellogg, and Asahel Curtis. West Ender Fannie Taylor took a special interest in photographing members of native tribes with whom she developed many friendships.

The Homestead Act was a political creation, produced by a range of interest groups but sponsored by the newly formed Republican party. In the decades that followed, the transition from a largely agrarian to increasingly industrial economy altered the political landscape and presented new concerns for farmers. By the 1890s, some of the most visible political issues revolved around the railroad companies, the monetary standard, and federal land policies. Every homesteader had a stake in how changes in government land policy might affect gaining title to a claim, as discussed in the Legislative Chronology in the Introduction. Railroads, welcomed as facilitating movement and transportation of goods, were also a source of bitter resentment as powerful lobbyists, recipients of large portions of the public domain, and for their rate practices. Farmers denounced the monopolistic rule of railroad companies and accused them of rate gouging. Similar charges were leveled against banks and supporters of the gold standard, which critics associated with elite control of the supply of money. The campaign to add silver to gold as the basis of currency, thereby increasing the supply of money, spurring inflation and making debts easier to pay gained momentum in more rural areas as gold became associated with the urban East, banks, and monopoly. Convinced that neither Republicans nor Democrats adequately represented their interests, various farm-based political groups emerged in the 1880s to champion agricultural causes, among others, and challenge the two party system. The most popular of these was the People's Party, a product of a largely grassroots movement known as Populism. As the battle between gold and silver backers reached a head in 1893, when a depression hit debtors - and many farmers carried debt - particularly hard, the People's Party became a force to be reckoned with. Populists won elections at various levels, including the governorship of Washington state. At the height of their strength, Populists voted to fuse with the Democratic Party in 1896, gambling that victory in the presidential election of that year presented the best chance of achieving their goals. Defeat of the "fusion" ticket by the Republican candidate William McKinley marked both the decline of the Populist party and the reconfiguration of politics in the United States since 1862: once the patron of homesteader, the Republican Party was in 1896 the farmer's enemy.

Populism was an important but brief episode in the history of farm politics. Other issues such as prohibition, immigration policy, suffrage, civil rights, and war came to the foreground at various times. Whether homesteaders, as a certain kind of farmer, voted in any distinguishable patterns, presents many opportunities for further study, particularly at the state and regional levels.

Although farmers only briefly constituted more than fifty percent of Washington's work force during the territorial and state years, federal censuses recorded that agriculture was still the second leading sector of state employment through 1930. Comparing the number of farms to the number of homestead claims in the censuses provides a rough indication that a sizeable percentage of Washington farmers were homesteaders. The question of how these homesteaders voted on the most salient political issues of the day remains largely unexamined. In local cases of political activism, such as petitioning congress for more government land offices, demanding the opening of railroad land for homestead claims, or resisting the inclusion of their lands in the national park system, the presence of the homesteader was clear, but where did homesteaders stand, for example, on the admission of Washington as a state in 1889, which rejected woman's suffrage and prohibition amendments while returning a large Republican majority? What role did homesteaders play in organizing state and local branches of the People's Party, and forging alliances with labor? When the Nonpartisan League came to Washington during World War I to recruit members, how did homesteaders receive its plan to help farmers - a program for state-owned grain elevators, mills, insurance and worker's compensation that was branded as dangerous radicalism and unpatriotic by its opponents? Did homesteaders join the campaign for good roads and influence what path they would take?

Some answers may be drawn from individual case histories, such as homesteader Peter B. Jersted, also known as Pete Benson, who was nominated to the position of Precinct Committeeman for the Ozette Precinct of the People's Party Central Committee in Port Angeles. Jersted attended the party's state convention in Tacoma on June 23, 1896, that determined how delegates would vote at the national convention held in Omaha later that summer. Another source of political activity was the state granges, an ostensibly non-political association that nonetheless provided forums for political education, organization, and solidarity. When residents of the West End of the Olympic Peninsula formed the Quillayute Valley Grange in 1917, most of its members were men and women from local homesteads. The remoteness of many Washington homesteads may have discouraged widespread involvement in politics, but for those that cast their vote, joined granges and political parties, and served at various levels of civil government, theirs is a history that can profit from greater attention in the classroom.

Homesteaders filled the time not occupied by work with the activities typical of rural America. Naturally, some leisure pursuits faded and others appeared with time. Outdoor recreation such as hunting and fishing blurred lines between work and play. Olympic Peninsula homesteaders visited the beaches, and hiked and camped in the nearby mountains. Some took up hobbies such as photography. Personal time indoors might be spent playing cards, reading, writing letters, or keeping a diary.

Nearby towns or big cities provided other options for entertainment. Men gathered in town as members of veterans groups, fraternal orders such as the International Organization of Odd Fellows or the Masons; women joined sister societies such as the Order of the Eastern Star, founded church groups and participated in a host of other organizations. Traveling shows or bands appeared in some of the smallest and most remote places. On the bill in Forks, WA one evening in the late 1920s was the Yager Brothers' Medicine Show, featuring dogs and monkeys as the star performers. Spokane or Seattle offered many other possibilities, particularly the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific world's fair. The AYP brought some rural residents - such as the Joss family from Cheney - to Seattle for the first time.

Holidays, dances, sporting events and societies provided occasions for communities to share leisure time in familiar surroundings. Jim Klahn recalled one Fourth of July on the Olympic Peninsula celebrated with fireworks, baseball, games, dances and horse racing.

Hardship and Misfortune

The homestead could be a tenuous place for couples and families. Homestead case files contain reports of wives "too sick" to live on the homestead; either an illness of the body or a veiled preference for a more urban lifestyle. Elsie Johnson remembered that "her mother cried a great deal, crying when they left St. Paul, crying when she cooked her first meal on a borrowed wood stove in a neighbor's cabin." (Dennis, 19) A few marriages did not withstand the experience, ending in divorce or abandonment. When faced with her husband's decision to abandon their claim for Canada, Mina Smith refused to leave and remained to raise her five children alone. Some found the isolation unbearable, the weather inhospitable, and the forests oppressive. In what may have been a common reaction to a rainy day in June, one Olympic Peninsula settler complained in his diary that he "Cut some more logs but could not work all day for it rained as usual. This tries a fellow's Christian Experience." Sickness or injury could prove disastrous. After an illness put his wife in the hospital, Edwin Blair took odd jobs in nearby towns to pay for the medical bills. His frequent absences from his homestead cost him his patent. Joseph Haumesser also lost his claim because he could not sufficiently prove he had established a permanent residence there. Haumesser's explanation of the circumstances that kept him from his land revealed the precarious nature of homesteading in the Olympics - a few tough breaks could make all the difference.

I cleared up a patch in the winter and planted a garden in the spring before I came out. I cannot remember the dates now but I put in a garden and after the 2nd or 3rd year oats or grass every year since 1891 and harvested these crops every year but one when I was sick in the hospital and had to go to work and earn money to pay bills for sickness when I came out of the hospital . . . This was my home but as I could not make a living there I had to go out and work for wages to get grub and tools and all my absences from the place were for this purpose.

Other accidents cost homesteaders their lives. Without hospitals or medical expertise in close proximity, a minor cut or complication during childbirth might be lethal. One farmer died from an infection that developed after he cut his hand on a nail while working on his farm. Out in the West End a resident remembered a burial ground near Beaver called "the Tragedy Graveyard by the early settlers because none of the thirteen people buried there died of natural causes."

Natural disasters presented other dangers. While felling cedars and burning stumps and slash on his homestead one summer day in 1891, Jacob Irely suddenly faced a conflagration that burned for two weeks and spread to some 3000 acres. A much larger fire that swept through 238,000 acres in Clark, Cowlitz, and Skamania counties in 1902 known as the Yacoult Burn killed 38 people. Olympic Peninsula homesteaders remembered well the night of the Great Blow Down of 1921, when hurricane-force winds brought down thousands of trees and several houses in the west end. After a flood destroyed Anton Kestner's first cabin, he moved to higher ground. Periodic drought, such as the one that lasted from April, 1934 to March, 1937, struck farms across the state.

UW Site Map © Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington